|

|

Hoosac Tunnel: Abode of the Damned?

An Exploration of the "Bloody Pit"

Article & Pictures

Site Visit: October 14, 2002 by Daniel V. Boudillion & Andrew T. Bowers

|

Introduction:

The Hoosac Tunnel, a railroad

tunnel beneath the Berkshire Mountains in Western Massachusetts, is said to be

one of the most haunted places in New England. It was an engineering marvel

of its age, completed in 1875, and nearly five miles in length. Yet, it would

cost 195 lives in various fires, explosions, and tunnel collapses, hence

earning its name among the crew at the "Bloody Pit." It has been the scene

ever since of hauntings . . . and even murder.

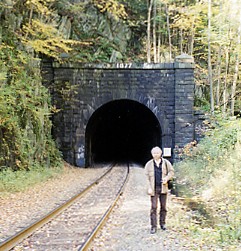

West Portal

History:

The Hoosac Tunnel was first proposed

in 1819 as an underground canal beneath the Berkshires in Western

Massachusetts as a way of providing the through traffic of goods and raw

materials between Boston and points West. A specially appointed

Legislative Commission of 1825 reported: "There

is no hesitation, therefore, in deciding in favor of a tunnel; but even if its

expense should exceed the other mode of passing the mountain, a tunnel is

preferable, for reasons which have been assigned. And this formidable barrier

once overcome, the remainder of the route from the Connecticut to the Hudson

presents no unusual difficulties in the construction of a canal, but in fact

the reverse; being remarkably feasible."

Profile of the Hoosac Mountain and Proposed

Tunnel

The situation of the day was that

there were no direct means between the finished goods coming out of Boston

and the raw materials of the West. The Berkshire Mountains were a decided

barrier to commerce. With the advent of steam locomotion the tunnel plan

was revaluated and re-proposed for railway traffic. Work was officially

commenced in 1851 by the

Troy and Greenfield

Railroad Company, "to build a railroad from the terminus of the Vermont

and Massachusetts, railroad, at or, near Greenfield, through the valleys

of the Deerfield and the Hoosac to the State line, there to unite with a

railroad leading to the city of Troy."

It was to take 24 years and $21,241,842 dollars to complete. There

were innumerable problems encountered, and new technology, both successful

and unsuccessful, was employed to meet the challenge.

Cutting the Tunnel & Construction

Facts

Initially the tunnel was to be

constructed using a 70-ton steam-driven boring machine "designed

to cut a groove around the circumference of the tunnel thirteen inches

wide and twenty-four feet in diameter, by means of a set of revolving

cutters. When this groove had been cut to a proper depth the machine was

to be run back on its railway; and the centre core blasted out by

gunpowder or split off by means of wedges."

The South Boston built

$25,000 machine cut a very smooth and beautiful hole into the rock for

about ten feet, and then it stopped forever.

This failed original tunnel

opening can be seen to the right of the East Portal.

Failed First Attempt on the Left

Following this failure,

the work was for a long time done by means of hand-drills and gunpowder.

But it was found that the most rapid progress that could be made with

hand-drills, under the most favorable circumstances, would not exceed

sixty feet a month at either Portal. This problem led to the introduction

of the compressed air Burleigh Drill, invented by Mr. Charles Burleigh, of

Fitchburg Massachusetts.

Burleigh Drill

The Hoosac Tunnel was the first

commercial application of Nitroglycerine. Nitro proved to be a very

powerful and extremely unstable explosive that resulted not only in

successfully blasting the length of the tunnel, but in killing dozens of

men in its use.

At Work in the Hoosac Tunnel

The tunnel was constructed by

driving two headings, one from the East and one from

the West. The total length of the tunnel is

4.82 miles long. The precision of the work was such that when the

headings met after approximately 2.5 miles of drilling each, the offset

error was approximately Ĺ inch. The original finished size of the tunnel

was 24 feet wide and 20 feet in height. However, recent work was begun in

1997 to grind an extra 15 inches to the height.

Grinding

Equipment

Photo by

Tom Freeman

The extraordinary job of aligning the tunnel and

keeping it on track to within 1/2 inch was due in part to the erection of

alignment towers on the East and West peaks above the proposed route of

the tunnel below. The below pictured tower is from the west peak

area, recently visited and photographed by noted regional expert

Jim Moore.

A second tower is said to exist in the east peak area.

West Peak Alignment Tower

Photo courtesy of Jim Moore

The tunnel, epically

in the Western portion, was run through

disintegrated mica

schist, which dissolved readily in water (of which there was plenty), and

was "utterly unmanageable." This horrible mixture of disintegrated rock

and water was referred to as "porridge." So much of the tunnel was beset

with soft rock and water problems that the only solution was to brick the

tunnel in long tubes of brick-work. In the end, over 30% of the tunnel

was sheathed in six foot thick brick walls and arches that required the

use of over 20,000,000 bricks.

Due to the difficulties of "porridge" at the the

West Portal, a second shaft was sunk about a half mile further up the

proposed line of the tunnel. This shaft, known as the West Shaft,

bypassed most of the gravel and water and allowed tunneling to advance

from the west at a steady pace. The depth of the shaft was 318 feet,

and was elliptical. The dimensions of the ellipse were 14 feet

east/west, and 8 feet north/south. The site of the shaft head was

located behind and up from a spur created of refuse rock dumped from

tunnel.

Hoosac Tunnel Final Specifications

The average depth of the tunnel

is about 1400 feet beneath the Hoosac Mountains, with the deepest point

being beneath the Western summit at 1718 feet - approximately 1/3 of a

mile.

There is a slight

grade to the tunnel resulting from an incline angling up

from both Portals to an apex at the middle near the opening of the Central

Shaft. The grade is very minor, rising only about twenty feet over 2.5 miles to facilitate the

runoff of water, which is omnipresent in the tunnel. Were it not for the

slight grade, you would be able to see pinpoints of light at both ends of

the tunnel from the middle point of the tunnel.

The construction manpower in

creating the tunnel was supplied almost entirely by Irishmen supplemented

with some Cornish miners for a typical work force of about 800 to 900

men.

East Portal Work Camp

Central Shaft & Disasters:

The Central Shaft was built somewhat of an afterthought, as a means

of ventilating the anticipated heavy coal exhaust expected to be built up

in the tunnel from locomotive traffic. The shaft is 1028 feet deep and

elliptical in diameter, the ellipse being 27 feet east/west, and 15 feet

north/south. The shaft reached the tunnel in August of 1870.

Central Shaft Head

When it was finally connected to the tunnel, the shaft was used to

hoist rock and ferry workmen in large copper buckets. The buckets

were attached to cross-bars of wood, which slide in a frame-work, of timber, thus preventing it from swinging

back and forth in its passage. A steam engine was used to hoist the

bucket at a rate such that the 1030 foot descent was a matter of but two

minutes. The miners "ride to and from their work, sometimes sitting

in the bucket, and sometimes standing on its rim, or on the cross-bars,

and holding on by the cable. Most of those at the central shaft are

Cornish miners, and their life-long experience in such holes in the ground

has made them reckless of danger. The fatal accidents that frequently

occur among them have no effect to in make them more cautious. When the

whistle blows for the 'shift' of hands, every man at the bottom wants to

come up in the first bucket, and generally the whole dozen of them do all

come up at once, two or three sitting in the bucket, and the rest standing

on the rim and the cross-bars, and clinging fast. If a man can get one

foot on the cross-bar and one hand on the cable, he had much rather come

up in that way than wait three minutes for the bucket to return for him."

Descending the Central Shaft

A second description of descending the Central

Shaft is from N. H. Eggleston witting in the March 1882 Atlantic

Monthly: "At every descent of the bucket it seemed as though those in

it were being dashed down the dark pit to almost certain destruction.

Speed was necessary, and the machinery was so arranged that the descent of

over a thousand feet was made in a little more than a minute. The

sensations experienced by those who descended the shaft were peculiar.

First, there was the sensation of rapid, helpless falling through space in

the darkness; then, as the speed was at last abruptly arrested, it seemed

for a moment as though the motion had been reversed, and one were being as

rapidly elevated to the surface again."

The Central Shaft was the scene of some the worst accidents in

building the tunnel. On October 17, 1867, an ill designed lamp called a "Gasometer"

leaked Naphtha fumes into the hoist house where it subsequently exploded,

sending the building up in flames. Thirteen men from subcontractor Dull,

Gowan, & White were working in the then 538 foot deep shaft at the time.

The first thing to things to fall on them were more than 300 newly

sharpened drill bits, followed by the hoist mechanism and burning sections

of the structure. With the collapse of the structure, the air-pumps

ceased working and, "Öthe poor fellows all perished there in the darkness.

Nobody knows how soon, or by what means they became aware of the danger

they were in; nor is it certainly known in what manner they died, but the

more probable conjecture is that they were suffocated."

Destruction of the Central Shaft

A fifty year old workman named Mallory who had superintended the

timbering volunteered to be lowered into the shaft. At 4:00 a.m. a rope

was fastened round his body and three lanterns were attached to him. He

passed out near the bottom of the shaft, but reported on recovery that there was no

hope for survivors as he was able to see nothing but water and burnt

timbers.

Within a few days the shaft filled with water and it was not until

a full year later that the shaft was fully emptied and bodies were

recovered. It was

discovered that not all the men had been crushed by the falling debris,

some had managed to build a raft but died from asphyxiation from the

fumes.

Open for Business

When the Hoosac

tunnel was officially opened on October 13, 1875, with the transit of a

passenger car of tourists, it was the one of the longest tunnels in the

world at 4.82 miles, second only to Mont Cenis in the Swiss Alps which

opened 4 years earlier and was 8.5 miles long. It was, however, the

longest tunnel in North America from 1871 to 1916, and is still the

longest transportation

tunnel east of the Rocky Mountains.

Ghost Stories:

Hoosac is a Native American word

for the region meaning "a stony place," and was considered by them an area

of sinister reputation.

So many were the deaths

involved in its construction that the Hoosac Tunnel that it was referred

to among the crew as the "Bloody Pit." After the accidents began piling

up many workers came to

feel that the tunnel was cursed and many of them refused to enter it

again. Some of the crew members simply walked off the job and did

not return.

Murder?

On the afternoon of March 20,

1865, three explosive experts named Ned Brinkman, Billy Nash and Ringo

Kelley decided to use nitroglycerine to continue their work on the

tunnel. They placed a charge and then ran back toward a safety bunker

that would shield them from the effects of the blast. Brinkman and Nash

never made it there however. For some reason, Ringo Kelley set off the

charge before the other men could make it to shelter. The two men were

buried alive under tons of rock.

Soon after the accident, Kelley

vanished without a trace, leading many to believe that the "accident" with

the nitro may not have been an accident after all. He was not seen again

until March 30, 1866 [almost exactly one year later] . . . when his body was discovered two miles

inside of the tunnel. It was found at almost the exact spot where

Brinkman and Nash had been killed. The authorities quickly deduced that

Kelley had been strangled to death. Deputy Sheriff Charles F. Gibson

estimated that he had been murdered between midnight and 3:30 AM that

morning. The death was thoroughly investigated but no suspects were ever

found and the crime went unsolved.

Restless Spirits?

In 1868 Mr. Dunn of the Hoosac Tunnel construction company reported that

workers "complained constantly of hearing a manís voice cry out in agony"

and refused to enter the half-completed tunnel after sundown

Dun and associate Paul

Travers investigated: "Dunn and I entered the tunnel at exactly 9:00

p.m.. We traveled about two miles into the shaft and then we stopped to

listen. As we stood there in the cold silence, we both heard what truly

sounded like a man groaning out in pain. As you know, I have heard this

same sound many times during the war. Yet, when we turned up our the

wicks on our lamps, there were no other human beings in the shaft except

Mr. Dunn and myself. Iíll admit I havenít been this frightened since

Shiloh. Mr. Dunn agreed that it wasnít the wind we heard. ... I wonder?"

In 1868 Mr. Dunn of the Hoosac Tunnel construction company reported that

workers "complained constantly of hearing a manís voice cry out in agony"

and refused to enter the half-completed tunnel after sundown

Dun and associate Paul

Travers investigated: "Dunn and I entered the tunnel at exactly 9:00

p.m.. We traveled about two miles into the shaft and then we stopped to

listen. As we stood there in the cold silence, we both heard what truly

sounded like a man groaning out in pain. As you know, I have heard this

same sound many times during the war. Yet, when we turned up our the

wicks on our lamps, there were no other human beings in the shaft except

Mr. Dunn and myself. Iíll admit I havenít been this frightened since

Shiloh. Mr. Dunn agreed that it wasnít the wind we heard. ... I wonder?"

Glenn Drohan, the correspondent who had first covered the 1867 Central

shaft disaster for the Transcript wrote: "During the time the

miners were missing, villagers told strange tales of vague shapes and

muffled wails near the water-filled pit. Workmen claimed to see the lost

miners carrying picks and shovels through a shroud of mist and snow on the

mountaintop. The ghostly apparitions would appear briefly, then vanish,

leaving no footprints in the snow, giving no answer to the minerís calls."

Glenn Drohan, the correspondent who had first covered the 1867 Central

shaft disaster for the Transcript wrote: "During the time the

miners were missing, villagers told strange tales of vague shapes and

muffled wails near the water-filled pit. Workmen claimed to see the lost

miners carrying picks and shovels through a shroud of mist and snow on the

mountaintop. The ghostly apparitions would appear briefly, then vanish,

leaving no footprints in the snow, giving no answer to the minerís calls."

On the night of June 25, 1872 Dr. Clifford J. Owen and James R. McKinstrey

the drillings operations superintendent traveled about two miles into the

tunnel and then halted to rest in the light of their lamps. Owens later

described the tunnel as being "as cold and as dark as a tomb." As they

rested they heard a strange and mournful sound. It sounded to Owens like

someone in great pain.

"The next thing I saw was a

dim light coming along the tunnel in a westerly direction. At first, I

believed that it was probably a workman with a lantern. Yet, as the light

grew closer, it took on a strange blue color and appeared to change in

shape into the form of a human being with no head." The light moved so

close to the two men that they could almost touch it. It remained

motionless, as though watching them, then hovered off toward the east end

of the tunnel and vanished. Owens later wrote that while he was "above

all a realist" and that he was not "prone to repeating gossip and wild

tales that defy a reasonable explanation" he was unable to "deny what

James McKinstrey and I witnessed with our own eyes."

On the night of June 25, 1872 Dr. Clifford J. Owen and James R. McKinstrey

the drillings operations superintendent traveled about two miles into the

tunnel and then halted to rest in the light of their lamps. Owens later

described the tunnel as being "as cold and as dark as a tomb." As they

rested they heard a strange and mournful sound. It sounded to Owens like

someone in great pain.

"The next thing I saw was a

dim light coming along the tunnel in a westerly direction. At first, I

believed that it was probably a workman with a lantern. Yet, as the light

grew closer, it took on a strange blue color and appeared to change in

shape into the form of a human being with no head." The light moved so

close to the two men that they could almost touch it. It remained

motionless, as though watching them, then hovered off toward the east end

of the tunnel and vanished. Owens later wrote that while he was "above

all a realist" and that he was not "prone to repeating gossip and wild

tales that defy a reasonable explanation" he was unable to "deny what

James McKinstrey and I witnessed with our own eyes."

On October 16, 1874 a local hunter named Frank Webster vanished near

Hoosac Mountain. Three days later, he was found by a search party,

stumbling along the banks of the Deerfield River. He was in a state of

shock, mumbling incoherently and falling down. He explained to his

rescuers that strange voices had ordered him into the Hoosac Tunnel and

once he was inside, he saw ghostly figures wandering around. He also said

that invisible hands had snatched his hunting rifle away from him and that

he had been beaten with it. He couldnít remember leaving the tunnel.

Members of the search party recalled that Webster did not have his rifle

when he was found and the cuts and abrasions on his head and body did seem

to bear evidence of a beating.

On October 16, 1874 a local hunter named Frank Webster vanished near

Hoosac Mountain. Three days later, he was found by a search party,

stumbling along the banks of the Deerfield River. He was in a state of

shock, mumbling incoherently and falling down. He explained to his

rescuers that strange voices had ordered him into the Hoosac Tunnel and

once he was inside, he saw ghostly figures wandering around. He also said

that invisible hands had snatched his hunting rifle away from him and that

he had been beaten with it. He couldnít remember leaving the tunnel.

Members of the search party recalled that Webster did not have his rifle

when he was found and the cuts and abrasions on his head and body did seem

to bear evidence of a beating.

In the fall of 1875, a fire tender on the Boston & Maine rail line named

Harlan Mulvaney was taking a wagon load of wood into the tunnel. He had

gone just a short distance into the shaft when he suddenly turned his team

around, whipped the horses and drove them madly out of the tunnel. A few

days later, workers found the team and the wagon in the forest about three

miles away from the tunnel. Harlan Mulvaney was never seen or heard from

again.

In the fall of 1875, a fire tender on the Boston & Maine rail line named

Harlan Mulvaney was taking a wagon load of wood into the tunnel. He had

gone just a short distance into the shaft when he suddenly turned his team

around, whipped the horses and drove them madly out of the tunnel. A few

days later, workers found the team and the wagon in the forest about three

miles away from the tunnel. Harlan Mulvaney was never seen or heard from

again.

1936.

One former railroad employee, Joseph Impoco, worked the Boston & Maine for

years. He firmly believed that the tunnel was haunted but he was not

afraid of the place. In fact, he credited the resident ghosts with saving

his life on two separate occasions. On one afternoon, he was shipping

away ice from the tracks when he heard a distinct voice telling him to

"run, Joe, run!" He looked back and saw a train bearing down on him!

"Sure enough, there was No. 60 coming at me. Boy, did I jump back fast!"

He looked around for whoever had called out his name, but there was no one

else nearby. Later, he would recall that he had distinctly heard the

voice before the train had appeared. He also added that he had seen a man

pass by, waving and swinging a torch, but he hadnít paid attention to

anything but the shout. The voice, wherever it had come from, had saved

his life. Six weeks after the incident, Impoco was again working on the

tracks. This time, he was using a heavy iron crow bar to free some fright

cars that had been frozen on the tracks. He was prying at one of the

steel wheels when he heard the loud, familiar voice again call out to

him. "Joe! Joe! Drop it, Joe!" the voice called frantically. Impoco

immediately released the bar and it was instantly jolted and thrown

against the tunnel wall by more than 11,000 volts of electricity! The

charge came from a short-circuited overhead power line. The unseen friend

has saved Joeís life again

1936.

One former railroad employee, Joseph Impoco, worked the Boston & Maine for

years. He firmly believed that the tunnel was haunted but he was not

afraid of the place. In fact, he credited the resident ghosts with saving

his life on two separate occasions. On one afternoon, he was shipping

away ice from the tracks when he heard a distinct voice telling him to

"run, Joe, run!" He looked back and saw a train bearing down on him!

"Sure enough, there was No. 60 coming at me. Boy, did I jump back fast!"

He looked around for whoever had called out his name, but there was no one

else nearby. Later, he would recall that he had distinctly heard the

voice before the train had appeared. He also added that he had seen a man

pass by, waving and swinging a torch, but he hadnít paid attention to

anything but the shout. The voice, wherever it had come from, had saved

his life. Six weeks after the incident, Impoco was again working on the

tracks. This time, he was using a heavy iron crow bar to free some fright

cars that had been frozen on the tracks. He was prying at one of the

steel wheels when he heard the loud, familiar voice again call out to

him. "Joe! Joe! Drop it, Joe!" the voice called frantically. Impoco

immediately released the bar and it was instantly jolted and thrown

against the tunnel wall by more than 11,000 volts of electricity! The

charge came from a short-circuited overhead power line. The unseen friend

has saved Joeís life again

In 1973 Bernard Hastaba set out to

walk through the tunnel from the North Adams entrance. He was never

heard from again.

In 1973 Bernard Hastaba set out to

walk through the tunnel from the North Adams entrance. He was never

heard from again.

In 1976, a researcher from Agawam, Massachusetts claimed to come

face-to-face with one of the local denizens. He described the figure of a

man in old-fashioned work clothing, backlit against a brilliant white

light.

In 1976, a researcher from Agawam, Massachusetts claimed to come

face-to-face with one of the local denizens. He described the figure of a

man in old-fashioned work clothing, backlit against a brilliant white

light.

In 1984 while in the tunnel with a railroad official, professor and

part-time ghost hunter named Ali Allmaker had the uncomfortable sensation

of someone standing close to her. She reports: "I

have only been in the tunnel once accompanied by a railroad official, and

can attest to the claim that it is an eerie place. I had the uncomfortable

feeling that someone was walking closely behind me and would tap me on the

shoulder at any moment or worse pull me into some unknown and unspeakable

horror at any moment."

In 1984 while in the tunnel with a railroad official, professor and

part-time ghost hunter named Ali Allmaker had the uncomfortable sensation

of someone standing close to her. She reports: "I

have only been in the tunnel once accompanied by a railroad official, and

can attest to the claim that it is an eerie place. I had the uncomfortable

feeling that someone was walking closely behind me and would tap me on the

shoulder at any moment or worse pull me into some unknown and unspeakable

horror at any moment."

In 1994 Kevin from Boston reported that while in

the old control room opposite the ventilation shaft he heard "whisperings"

and a "shape" about three feet tall and completely black staying just

outside of the edge of his flashlight beam. "It always stayed just outside

the beam about 20 feet distant, I have to conclude it was the light that

kept it away from me. What I saw was real and moved with deliberation and

I didn't have reason to believe it was friendly."

In 1994 Kevin from Boston reported that while in

the old control room opposite the ventilation shaft he heard "whisperings"

and a "shape" about three feet tall and completely black staying just

outside of the edge of his flashlight beam. "It always stayed just outside

the beam about 20 feet distant, I have to conclude it was the light that

kept it away from me. What I saw was real and moved with deliberation and

I didn't have reason to believe it was friendly."

Locals in the area still claim that strange winds, ghostly apparitions and

eerie voices are experienced around and in the daunting tunnel. Some

researches have left tape reorders in the tunnel and have reported hearing

what seems to be muffled voices when they play back the tape. There

is also rumor of a "hidden room" in the tunnel. The room is said to

be bricked up and house unspeakable horror. Balls of bluish light

and "ghost lanterns" are also said to haunt the tunnel, and legends abound of "ghost hands"

both pushing people in front of oncoming trains, as well as pulling them

to safety. (Make up your minds!)

Locals in the area still claim that strange winds, ghostly apparitions and

eerie voices are experienced around and in the daunting tunnel. Some

researches have left tape reorders in the tunnel and have reported hearing

what seems to be muffled voices when they play back the tape. There

is also rumor of a "hidden room" in the tunnel. The room is said to

be bricked up and house unspeakable horror. Balls of bluish light

and "ghost lanterns" are also said to haunt the tunnel, and legends abound of "ghost hands"

both pushing people in front of oncoming trains, as well as pulling them

to safety. (Make up your minds!)

Field Investigation:

"This ride into the tunnel is far from being a cheerful

one. The fitful glare of the lamps upon the walls of the dripping

cavern,óthe frightful noises that echo from the low roof, and the

ghoul-like voices of the miners coming out of the gloom ahead, are not

what would be called enlivening."

- The Hoosac Tunnel,

Scribner's,

December 1870

Indeed, the Hoosac

Tunnel in not an inviting place. On October 14, 2002, Andrew

Bowers and I walked the length of the tunnel in hopes of seeing a spook or two,

and perhaps get pushed in front of a train. The usual shenanigans.

East Portal

It was quite the

adventure. We entered he tunnel from the East Portal around 9:00

a.m., walked the length to the West Portal, stopped for a "non-lunch"

(more on that later) and then walked back again. We did not arrive

back at the East Portal until around 4:00 p.m. The entire trip was a

little over 6 hours underground. And, we emerged grimed by over a

century of soot.

East Portal ~ June 2002

It was a sunny day, and we made the surprising

discovery that a little sunlight goes a long way in a tunnel. After

your eyes adjust to the dark, even the small amount of sun from the

tunnel's opening was entirely enough to light our way, at least dimly.

In fact, we did not even bother with flashlights until we had progressed

well over a mile, and then it was simply to have a look at the

architectural features of the place rather then a need for lighting.

This is not to give the impression that it was well lit, it is just to

say that in my experience, you can walk this tunnel on a sunny day without

a flashlight. I do not recommend this, however.

Going, going, gone. . .

the third photo was taken after walking an

hour

First, there are electrical cables running the

length of the southern wall. These are waist height, and conveniently

placed in such a way that if you were to hold them like a had rail you

would also be standing in six inches of water. Not a good idea.

Second, 9.5 miles of railroad tracks is brutal on the feet. And you

really do have to walk on the tracks. The berm to either side is

either crushed rock or inches of muck. The only relatively dry and

stable ground were the tracks themselves. Also, walking between the

rails keeps you from falling off the berm and into the water. We

stumbled a lot. Third, the bricks are collapsing from the bricked

sections of the tunnel. Individual bricks jumping out of the

ceiling. Sheets of brick collapsing out from the walls. Not

that a flashlight will stop them, but you might feel safer.

According to IRONFIST: "Although

not a particularly difficult mission to prepare for, the threat within the

tunnel is real. Large freight

trains pass through at random hours, leaving behind them a potentially

lethal amount of diesel fuel, one hundred year old bricks and archway

supports fall onto the tracks at will, and live electrical wires dance in

the dark."

Inside Tunnel ~ Note Brickwork

Photo by Jeff Sumberg

There were many interesting features we noticed

as we went along. Every 200 yards or so there were old field telephones

set in the wall for emergency train use. These were set in alcoves

and lighted. The electrical cables were everywhere, especially on the

south wall, and had the nasty habit of often lying in pools of water.

The brick sections of the the tunnel were particularly interesting.

Central Shaft

After about two hours in we began to hear a mechanical

noise and see a spark of light far ahead. We debated for some time

whether it

was a train not. Thing is, there really is no place to go in the

tunnel in the event of a train. It is a press-up-against-the-wall

and hope for the best situation. The light appeared to be bobbing,

but we eventually realized that this was only a trick of the eye. (Same thing

when you stare at a star at night - it appears to jump around after awhile

due to the optic nerve getting tired.)

After waiting awhile, and noticing that the

light was not getting any brighter, we resumed our journey. The

mechanical noise became louder, and was accompanied by an ever

stiffening breeze. We soon realized we were approaching where the

Central Shaft opens down into the tunnel. There is a large fan

situated 1000 feet up the shaft in the shaft house that draws air out of

the tunnel at great velocity. Both the breeze and the noise were

from the fan.

Black Hole of the Central Shaft

The opening to the Central Shaft was a dark hole

curving up into the south side of the tunnel. I have heard that some

technical climbers have tried to climb the shaft, but having had a good

look at it, I would doubt even the nut-jobs at IRONFIST

would try it. Across the tracks from the Central Shaft opening is a

small brick room built into the rock. There were various old pieces

smashed electrical equipment in it. It had a window overlooking the

tracks and perhaps it was a manned station at one point in the tunnel's

history. At the moment it seems to be a destination for the

heartiest of partiers. The graffiti crowd had discovered it too, and

mementos of many a dark journey had been carved in the woodwork and

painted on the walls. One such memento proclaimed that "Ozzy lives

here," presumably this was

before his recent return to stardom and the purchase of that mansion.

West Portal as seen from Central Shaft

The light we had been seeing turned out to be

the spark of sunlight glinting in from the West Portal opening. Because the track

has a slight grade to each end, with the apex at the middle, we did not

see the West Portal light until we had risen high enough on the grade.

Ghosts

Interesting as all this was, we were here for

spooks, and spooks we demanded. We literally walked the first two

hours in the dark hoping that would be conducive to spook attraction.

After that we lit candles and walked with those. It

was great ambience, those candles - but no spooks. We had heard there

was a place in the tunnel referred to as the "Hoosac Hilton." This

was supposed to be an area where a large section of the tunnel collapsed

killing dozens of workers. It was supposed to be obvious because the

tunnel opens out in a cavernous chamber there. We never found the Hilton. Of course,

we were walking in the dark, but even so we were still able to just make

out the tunnel walls on either side, and I swear we never came to an area

where the tunnel opened out into a large chamber area.

Spirits of the Damned?

Several times during the first two hours I took

pictures in the dark to see if anything spooky would like to show itself

on film.

Nobody that I am aware of decided to pose, but I did get one photo of some

interesting specks and globes of light that appear to be floating in the

tunnel. Are these souls of the dearly departed?

Still haunting the site of their gristly and untimely demise? Or

just . . . specks?

West Portal

The walk from the Central Shaft to the West

Portal seemed to take forever, and I have since learned that indeed - it is a

longer walk than the East Portal section. And, the West half is the wet

half. Water everywhere. Water gushing out of the walls, water

raining out of the ceiling, water filling both sides of the tracks.

And of course the mud. Not just any mud, but disgusto-mud mixed with

decades of soot and cinders. It dried on my boots like cement.

We slogged our way to the West Portal.

This end has an interesting feature - a huge garage door. I kid you

not. This door is such that it can roll down and completely cover

the West Portal opening. I have since heard it had something to do

with snow getting in or "keeping the bears out," but it seems rather unlikely. Frankly, I have no

idea why it is there.

However it does bring to mind an entry from a

ghost-hunting website that has long since died of shame. Apparently

four intrepid ghost hunters, two men and their girlfriends approached the

West Portal in broad daylight one winters day. They felt "chills"

from the "bad vibes." After much coaxing by the girlfriends, the two

men entered the West Portal and went several dozen feet. It was

there they heard the sounds of "body bags falling from the ceiling", and

ran back to the womenfolk. What body-bags falling from the ceiling

sound like, I don't know, but perhaps they had prior experience with this.

All of which brings to mind the wife of friend who walked part of the old

RR tunnel in Clinton, and who also reported "body-bags."

Andy at the West Portal

I was starved and had been looking forward to

lunch at the West Portal. Andy had promised to bring lunch. We

climbed up on the granite foundations of the portal and opened our packs.

Andy took out a candy bar and ate it. Then he had some water.

That was it - no lunch was forthcoming from the pack. I watched him

eat the candy bar. I thought hard bitter thoughts. I wondered

if a train came through if he would get pushed in front of it.

More Ghosts?

The walk back was a cold, wet, and hungry one.

After about several hours on the return walk we noticed that the light from the

West Portal seemed to have a different gleam to it - it didn't seem right.

After some observation we finally realized that it was incandescent and

coming towards us - and entirely silently. Was it the spooks at

last?

We looked for a place to hide in the event it

was a train. Somehow I had the feeling we probably were not supposed

to be in the tunnel, and felt it was probably best not to be seen.

There really was no place to hide though - just tunnel. However,

where the brick sections butted up against the non-brick sections, there

was a slight recess into the wall of about a foot. We decided to

scrunch back into the recess and await events. Events turned out to be one

of those railroad company pickup trucks - the kind that are adapted to

ride on the tracks. It had its bights on and seemed virtually

silent. We pressed into the recess and watched it glide by, barely

an arms length away. I can't imagine they didn't see us.

Comin' Through!

We continued our journey back, quickening the

pace. We passed the Central Shaft section and after awhile could

again see the spark of light from the East Portal. We also noticed a red

light. At this point neither of us equated lights with spooks, but

with railroad personnel. We watched and waited and found another

recess. Our efforts were rewarded with the realization that we had a

freight train approachin'. It came on real slow. They must not

go any faster that 10 or 15 miles per hour in the tunnel. The entire

tunnel began to vibrate hideously long before it got to us. When it

did get to us even the rock was shaking and I wondered why the bricks

didn't all fall as I pressed up against the wall. After the engine

went by it was completely dark, and quite a sensation hearing car after

car slam and rattle by only an arms length away in the pitch dark.

Once the train passed, we had new developments -

we could no longer see the light from the East Portal. It was like

something was blocking the end of the tunnel. As we

continued walking we gradually began to see the portal light again and realized that there was

so much black diesel exhaust fumes from the train that it completely

blocked all the light.

To quote again from N. H. Eggleston in the March

1882 Atlantic Monthly (about how a perpetual cloud of smoke from up

to forty trains a day made it impossible to see more than a few yards in the

in either direction when in the tunnel): "No artificial light, not even the

headlights of the locomotives, can penetrate the darkness for any

considerable distance. The engineer sees nothing, but feels his way

by faith and simple push of steam through the five miles of solemn gloom.

If there is any occasion for stopping him on his way through the thick

darkness, which may almost literally be felt, the men who constantly

patrol the huge cavern to see that nothing obstructs the passage, do not

think of signaling the approaching train in the common way. They

carry with them powerful torpedoes, which, whenever there is occasion,

they fasten to the rails by means of screws. The wheels of the

locomotive, striking these, produce a loud explosion, and this is the

tunnel signal to the engineer to stop his train."

Our final adventure over for the day, we walked

out of the tunnel about an hour later, grimed from head to toe.

Those walls were as sooty as a chimney.

Footsore and Hungry

Photo by Andy Bowers

Observations & Mysteries:

The tunnel is a gritty, dirty, cold and muddy

place, and physically taxing. Freight trains blast through on

regular basis. Electric cables lie in pools of water. There is

no lunch anywhere. If you enjoy such adventures, you are

there. It is not for the timid or casual hiker. The brave lads

from the Ghost-Hunters website only got 30 feet, in broad daylight,

before scampering off in fear.

Some things remain mysteries. We were

unable to locate or verify the Hoosac Hilton. There were certainly

many fatal cave-ins involved in the making of the tunnel, but it seems odd

that one of this supposed size and loss of life has gone unrecorded.

Neither did we find any trace from the inside of the tunnel of the old

West Shaft. Nor have we located the exact site of the shaft head on

the mountain side. Was the shaft entirely filled, or simply capped

and bricked off at both ends? Also, the "Hidden Room of Hoosac"

remains a mystery. Its unspeakable horror still remains unspeakable.

As for spooks, I was quite disappointed. I

guess evil had the day off. Even walking most of the tunnel with no

light whatsoever was not enough to entice the damned for a picnic in the

crypt. I guess they knew there would be no lunch. . . .

Helpful Tips:

First and foremost, any trip into the tunnel

should be approached as a spelunking adventure, and with all the necessary

precautions. The tunnel is like a cave that at its deepest point is

2.5 miles from an entrance - not a good place to be if things go wrong.

According to the camy-clothed para-wieners of IRONFIST: "Despite what many

believe about the Hoosac Tunnel, it is not as simple an operation as it

seems. The

IRONFIST expeditionary team has had years of practice in the most

difficult of situations and questionable locales such as the Hoosac Tunnel

and has therefore honed their skills like none other. Their

classification of the Hoosac Tunnel as 'easy' should not be taken

literally, as the group has encountered many dangers within, including

trains, noxious gases, and unfriendly locals."

If you go round trip, expect the journey to take at least 6

hours. Bring a small "AA" Mini-MagLight style flashlight. You don't

need a big one and it will only strain your arm carrying it for 6 hours.

Bring a spare Mini-MagLight and several sets of reserve batteries. Be careful

about your light - railroad personnel in trucks and on foot can see a

flashlight real well in the tunnel. Wear a hardhat. One falling

brick could possibly kill you. And falling bricks are a real hazard.

Its cold in there, bring an extra sweater for your pack. Wear waterproof

footwear - and remember, whatever you wear you will be wearing for a jarring

10 mile hike. And, the diesel exhaust fumes could be life-threatening

in that confined space. Of course, you won't need any of my advice if

you are one of those nut-jobs from IRONFIST.

Links and References:

East Portal: Head west on Route 2 (Mohawk

Trail) to the center of the town of Florida. One half mile before the

Eastern Summit, take a right on Church Road, a steep dirt road. At the

bottom take a right onto Whitcome Hill Road. Take a left on River Road

at the Deerfield River. About one half mile or more on the right is a

railroad crossing. The East Portal is up the tracks on the left.

West Portal: Head west on Route 2 (Mohawk

Trail) past the

Western Summit. West Shaft Street is on the left about 1.5 miles

past the hairpin turn. The West Portal is not observable from the road.

You will need to park on the right just before where the road bends right and

goes down into North Adams. The West Portal is 3/10ths of a mile due

west through the woods.

Central

Shaft, Shaft Head & Fan Building: Head west on Route 2

(Mohawk Trail) through the town

of Florida. Central Shaft Road is on your left about 2 miles past

Whitcomb Summit. The shaft-head

fan building is about 1.5 miles on the left.

Central Shaft Head & Fan Building

Photo by Jeff Sumberg

Websites:

Jerry "Ringo" Kelley presents

The Hoosac Tunnel: Now and

Then

The most comprehensive Hoosac Tunnel

website.

An article from Scribner's

December 1870 issue:

Building the Hoosac

Tunnel

Hoosac Tunnel Vintage Postcard Picture Gallery:

Hoosac Tunnel

History and Haunting of America:

Ghosts of the Bloody

Pit

Facts & Stats about the

Hoosac Tunnel

Books:

A

Pinprick of Light: The Troy and Greenfield Railroad and Its Hoosac Tunnel

by Carl R. Byron

About the

Authors:

Neither Dan

or Andy are nut-jobs from IRONFIST.

To boudillion.com Home Page

Field

Journal

Copyright © June 2003 by Daniel V. Boudillion

|