|

|

Nashoba Hill: The Hill that Roars

Vision Quest and Nashoba Praying Indian

Village

Field Investigation © by Daniel V. Boudillion

|

Note: this is the full

text of the abbreviated version published in the book Weird Massachusetts

Expanded & Revised

12-2009

Introduction

There is a very

special hill in Littleton, a hill that roars. The Indians thought

the winds were pent inside; the Colonials said it sounded like cannons;

some folks climbed it to await the rapture; and others erected a stone

altar on its top. It’s a well-known hill, famed these days for its ski

slopes. But its history is far more strange, and ongoing, than anything

that has ever swooshed down its slopes or taken the chair-lift. Gather

around the ski lodge fire, friends, and hear the strange tale of Nashoba

Hill: of a dark king under the mountain and an island village of vision

quests and shamans.

.Section 1: History & Legend

Nashoba Praying Indian Village

Littleton,

Massachusetts was originally a Praying Indian Village. Back in 1646,

Rev. John Eliot, known as the Apostle to the Indians, began an effort to

organize the Massachusetts Indians into Christian Villages. With the

backing of Cromwell’s England and 12,000 pounds sterling, he began a

long-term mission to the Massachusetts and translated the Bible into

Algonquin in 1663. Littleton,

Massachusetts was originally a Praying Indian Village. Back in 1646,

Rev. John Eliot, known as the Apostle to the Indians, began an effort to

organize the Massachusetts Indians into Christian Villages. With the

backing of Cromwell’s England and 12,000 pounds sterling, he began a

long-term mission to the Massachusetts and translated the Bible into

Algonquin in 1663.

Although he was a

Puritan, Eliot was also a humanitarian and he felt that the best way to

assure their survival in the midst of heavy English land-pressure was to

organize the Indians into English towns and lifestyles. They were to

convert to Christianity, have deeded towns, live in English houses, wear

English clothes, and worship Puritan style in Meeting houses.

John

Eliot

.

Between 1651 and

1658, Eliot and his assistant Daniel Gookin organized seven Praying

Indian Villages in Massachusetts Bay Colony, and Nashoba was the sixth.

All told there were at least 14 such villages in Massachusetts with

between 45 to 60 inhabitants each.

The

UP-BIBLUM GOD,

the Bible translated into Algonquin

1663 edition

In an interesting

twist, Eliot allowed the Indians to choose the sites of their new

Villages. The local Concord Indians led by an early convert, their

Sachem Tahattawan, requested the

"nashope"

lands close by. With such latitude to location, it would not be

unexpected for the Indians to choose places that were special or

important to them. It is also known from Eliot that

"nashope"

was Tahattawan’s main residence, again marking these lands as desirable.

The Indian

Plantation of Nashoba [also spelled Nashobah] was formally granted by

General Court in 1651 and was laid out in a lozenge-shape carved from a

gore of unsettled lands situated between Groton, Chelmsford, Concord,

and Lancaster. Its sides were approximately 3 x 4 x 4 x 4 miles in

length and the area encompassed most of current day Littleton and a

portion of Boxborough (which was formerly Littleton). The Indian

Plantation of Nashoba [also spelled Nashobah] was formally granted by

General Court in 1651 and was laid out in a lozenge-shape carved from a

gore of unsettled lands situated between Groton, Chelmsford, Concord,

and Lancaster. Its sides were approximately 3 x 4 x 4 x 4 miles in

length and the area encompassed most of current day Littleton and a

portion of Boxborough (which was formerly Littleton).

The Village

thrived until King Phillip’s Indian War in 1675-76, when the Nashobas

were rounded up and dumped on Deer Island in Boston Harbor to freeze and

starve. Only a handful survived to return. The Plantation was rapidly

sold to English settlers seeking land and by 1714, it was completely in

English hands as the Town of Nashoba, and re-incorporated as the Town of

Littleton in 1715. The surviving Indians were given the Indian New

Town, a 500 acre tract of rocky hill between and including portions of

Nagog Pond and Fort Pond (which was named after the Indian fort there).

Nashoba Indian

Plantation 1654 and Town of Littleton 1988

click to

enlarge

.

Note: Nashoba Plantation is in

red, and Littleton is marked in

blue. The red square of Nashoba Indian Plantation was

incorporated as the Town of Nashoba in 1714. The next year the

name was changed to Littleton. Note how the shape of the town has

changed over the years. For instance, the lower left corner became

part of Boxborough, and Concord Village (Powers Farm) was added to the

right side of town.

What does "Nashoba" Mean?

Nashoba is a word

of many meanings. When applied to the Nashoba Praying Indian Village,

it means the Place Between the Waters. (These titular waters were Nagog

Pond and Fort Pond, and less significantly, Long Pond.) When applied

to Nashoba Hill, it means the Hill that Shakes. It is from Nashoba Hill

that the early English settlers said the booming and rumblings

emanated. Sachem Tahattawan certainly did choose a place of special and

unusual qualities, intentional or not.

Nagog Pond & Fort

Pond

.

Note: The "Place Between

the Waters" is located between Nagog & Fort Ponds.

Where the Winds are Pent

Daniel Gookin in

his Historical Collections of the Indians in New England,

(written in 1674, and published in 1692), identifies an Indian belief

that unusual noises were associated with a pond in Nashoba: Daniel Gookin in

his Historical Collections of the Indians in New England,

(written in 1674, and published in 1692), identifies an Indian belief

that unusual noises were associated with a pond in Nashoba:

"Near

unto this town [Nashoba] is a pond, wherein, at some seasons, there is a

strange rumbling noise, as the Indians affirm; the reason thereof is not

yet known. Some have considered the hill adjacent as hollow, wherein

the wind, being pent, is the cause of this rumbling."

Commenting on this

passage by Gookin, Rev. Edmund Foster of Littleton said in his 1815

Century Sermon that,

"The

above pond above mentioned must be Nagog . . . it lies on the eastern

extremity of this town."

Nagog Pond at

Winter Solstice

.

Creative Commons:

Courtesy of Muffet

The

"adjacent

hill"

is not specifically identified by Gookin, but John Mitchell in

Trespassing (1998) indicates that it is a low hill to the

"Northwest"

of Nagog Pond, and paints this florid picture,

"[the

hill] was hollow and the four winds were pent up inside. Periodically

they would attempt to escape, and at these times … terrible roaring and

growls and rumbles were issue forth from within the hill. The very

earth would shudder, massive rocks would shift from their beds, trees

would sway and creak, and were it not for the intercession of the

shamans, the earth might have cracked open and revealed the dark,

boiling innards."

Nashoba Hill

.

Note: View from the Packard Farm on Great

Road.

Eyewitnesses of

the rumblings in earlier centuries clearly identify the spot as Nashoba

Hill. John Warner Barber in his 1841 Historical Collections

relates,

"The

report of the strange noise, heard occasionally in this pond, was not

without foundation. But the noise was not within the water, as they

[the Indians] imagined, but from a hill. Lying in a north-west

direction, and about half a mile distant form the pond, partly in

Littleton and partly in Westford, known by the name of Nashoba Hill."

Other odd

earth-noises heard in Nashoba at that time were loud humming sounds that

emerged from the beneath the Praying Indian Village. This was recorded

in the writings of John Eliot, who knew the village well and lived there

off and on while preaching. A Littleton Town Clerk’s report from 1896

references Eliot in this regard,

"He

came to this place to visit his wards, and in his writings are found

allusions to it, among others to the noises in Nashoba Hill."

|

"Elliot, The First

Missionary Among The Indians"

John Chester Buttre,

1856

|

"Eliot's Pulpit",

Boxborough

Near Swanson

Road, since destroyed |

|

.

.

Note: Elliot preferred to preach from the

top of large boulders to the extent that these locations became known as

"Eliot's Pulpits." There are a number of such Eliot's Pulpits in

Massachusetts. The one in Boxborough, pictured above, was adjacent

to what would become the Nashoba Praying Indian Village, and is where he

often preached to the Nashoba Indians. See the

Picture

Glossary of New England Lithic Constructions for further information

on Eliot's Pulpits. A more representative picture of Eliot's

preferred mode of address, if otherwise inaccurate, is

here.

He was also known to preach beneath large trees, the

Eliot Oak

in the Praying Indian Village of Natick being one such example.

|

Interestingly, for

about a week in the early 1980s a humming sound was heard to emanate

from the ground in Littleton. It sounded like it was coming from the

North and proceeded Southwards, and was most audible near the

Congregational Church on King Street.

Humming sounds

from the earth are not without precedent, the

"Taos

Hum"

of Taos, New Mexico being the best known of such phenomena.

Water Monsters

An Indian belief

related by John Mitchell in Trespassing is that Nagog Pond was

supposedly home to a water monster in the time of the Nashoba Praying

Indian Village. According to Mitchell, Ap’cinic was a water beast that

lived deep in the pond. It had horns and a

"gnashing

beak,"

and would

"reach

up out of the waters of Nagog at certain times and draw the entrails of

passing villagers down into its depths."

Its tentacled arms were said to feel along the shore for victims.

Nagog Pond

Currently Nagog

Pond is the town of Concord’s water supply and prior to that it was a

resort lake with boating, the Nashoba Inn, and cottages nearby. I have

never heard of anyone being pulled in by Ap’cinic, but plenty of people

have been pulled out by the Acton Police for illegal fishing.

|

Indian Water

Monsters

Piasa sketch & Uktena-like

petroglyph

Note the horns and long tail

The Piasa picture is from a sketch made

by Jean-Bapiste Framquelin in 1678 of an Indian painting on the

limestone bluffs on the Mississippi River in Alton, Illinois.

Although modern drawings show the Piasa with wings, the Framquelin

sketch and the 1673 Marquette description depict the Piasa as

water monsters, as follows:

"They are as large As a calf; they

have Horns on their heads Like those of a deer, a horrible look,

red eyes, a beard Like a tiger's, a face somewhat like a man's, a

body Covered with scales, and so Long A tail that it winds all

around the Body, passing above the head and going back between the

legs, ending in a Fish's tail."

It was not until 1836 that it

erroneously became a "bird" and was depicted with

wings.

More Easterly, and more in Algonquin

territory, there are similar traditions of horned serpentine water

monsters, such as the Maine Abenaki Pita-Skog, meaning "Great

Snake," and the eastern Uktena, meaning "Horned Serpent."

Further, there is also an Underwater Panther in Eastern Native

tradition.

For more on the Piasa and links to

winged anomalous beings, see:

Mothman &

the Thunderbird: A Striking Resemblance Between Two Creatures of

Legend.

|

A Haunting Landscape: Sarah Doublet Forest

Some people feel

that Nashoba is haunted, specifically, the area known as the Sarah

Doublet Forest on the rocky hill squeezed between Nagog Pond and Fort

Pond. This is the 500 acre area set aside in 1714 for the remaining

Indians after they sold off the Village. It remained in Indian hands

until 1736 when the last surviving member, Sarah Doublet, passed away.

It is considered to be central to the old Village, and if Tahattawan did

chose

"nashope"

for its special qualities, the 500 acres would particularly display

those unique qualities.

"500 Acres Land.

Indian Reservation."

1714 Littleton

Proprietor's Map

Courtesy Littleton

Historical Society

This rocky hill is

a strange and inspiring landscape indeed. The bare bones of the earth

are exposed in bleak gray ledge, cliff, and strange long humps of

granite bedrock that look like beached whales. Narrow trails wind

between them, and stone walls of inexplicable origin proliferate.

Traces of the old village remain: acres of corn planting mounds, three

worked-stone springs, a hollowed and smoothed rock surface, and

artifacts unearthed on the western

slopes*. I’ve been told by a retired

Professor that the fire-blackened rock faces are the marks of Indian

fires. Also in evidence are veins of white quartz, a crystal structure

prized by the shaman of old.

.

*Note: An elderly man who owned a summer

camp on Fort Pond related this story: when he was a boy he used to fire

his .22 rifle from the back steps of the cottage into the slope of the

hill across the lane. For safety's sake, he dug out a shooting

butt in the hillside, and in doing so unearthed a considerable number of

stone Indian artifacts. The location and type of artifacts have

led some to believe that this hillside was a burial area.

Corn Planting

Mounds

.

Note: There are very few surviving Indian

corn planting mounds in existence. If these are real mounds, as we

suspect, then they are of considerable historical significance.

About 15 years ago we were able to interest the State Archeologist in

these mounds to the extent that he set up a date to meet us here and

look at them. Unfortunately, due to an illness, this was cancelled

and never rescheduled.

Freshwater Springs

in the Sarah Doublet Forest

.

Note: There are three worked-stone springs

in the Sarah Doublet Forest. The one to the left has a capstone

and a cleared channel. In the 30 years I have visited this

locations I have never seen this spring dry - with the one exception of

the occasion I took the photograph. The spring to the right

emerges from under ledge-rock. A channel has been cleared for the

water to flow. The third spring is now the water supply for a

summer cabin on the shore of Fort Pond. The springs are

significant - any Indian settlement would require fresh water (lake

water is not a good idea to drink) and would have provided a year-round

supply.

|

The Indian Fort

at Fort Pond

By

Daniel V. Boudillion

14

December 2009

Fort Pond in Littleton was named after

the Indian Fort of the Nashoba Praying Indian Village era of 1651

to 1714. This was a small palisaded enclosure, similar

to other Indian forts recorded by the Puritans in the 1675/76 King

Philip's War. It is recorded that the Nashobas would abandon

the fort and leave the area the minute the Mohawks (their

ancestral enemies) would appear in the area, so it likely that the

either the fort was poorly constructed or there were not enough

men to defend it, or both. However this may be, its exact

location has been lost, but there are several possible places it

could have been.

For the rest of the article click

here.

|

Worked Stone and

White Quartz at Sarah Doublet Forest

.

Note 1: The stone to the left is in a small

Colonial quarry. A large oval bowl of unknown purpose and origin

has been worked into the stone. It does not appear to be a lye

leaching stone, nor does it look like a typical corn-grinding stone.

In any event, the stone was left intact and carefully quarried around,

suggesting it was of significance. It may also indicate an Indian

origin as Native Americans were often employed as stone cutters in

Colonial times, and may have preserved the stone.

.

Note 2: The stone to the right bears

white-quartz, a stone significant to Native Shaman at the time.

There is also a second vein of white-quartz in the western slopes of the

hill. This would have been part of the of significance of Nashoba as a "special place."

There are three

turtle effigies to be seen here, as the turtle was sacred to the

Algonquin-speaking peoples of Massachusetts. The largest is a

collection of boulders on the lower eastern slopes that appears like a

giant turtle crawling up from Nagog Pond towards the hilltop. A

carapace stone is further up the hill and a small but elegant stone-pile

turtle effigy is in the woods near the eastern shore of Nagog.

Turtle Rock at

Sarah Doublet Forest & Nagog Pond Turtle Effigy

Turtle Carapace at

Sarah Doublet Forest

.

Photo enhancement

courtesy of Tim

MacSweeney

Colonial Cannons: The Shooting of Nashoba Hill

The early English

settlers were also aware of the strange boomings and rumblings in the

area, especially from within Nashoba Hill. It was so loud that they

likened the sound to cannon shot, and said it was as though an army was

trapped inside the hill.

According to

Barber in 1841,

"A

rumbling noise, from time to time has been heard from this hill ever

since the settlement of this town, it has been repeated within two years

past [1839-1841], and is called

'the

shooting of Nashoba Hill.'"

The first English

settlement in the area began with Ralph Shepard and his son-in-law

Walter Powers in 1666. They lived in an area between Nagog Pond and

Nashoba Hill called Concord Village that shared a common border with the

Praying Indian Village. The settlement was nearer to the Hill than the

Pond and Powers actually lived on the lower slopes of Nashoba Hill as

early as 1675 in the old Garrison House. Both families would have heard

these

"cannon

shots"

and are no doubt the people referred to as hearing the noises

"ever

since the settlement of this town."

Walter Powers'

Garrison House Well

.

Note: The Garrison House

was situated on the lower slopes of Nashoba Hill to the right of the

well. There is a local tradition that there was a tunnel leading

from the Garrison house into the side of the hill. The Garrison

house is long gone, but the rumors of the tunnel persist. It is

possible this is a folk memory of a chamber that was said to have been

in the vicinity.

The rumblings

became part of the fabric of Littleton life, so much so that a one-page

write up on Littleton in Nason and Varney’s popular a popular 1890

almanac, the Massachusetts Gazetteer, includes a mention of it:

"The

most noted eminence is Nashoba Hill, on the eastern border. From

this, since first settlement, a rumbling noise is sometime heard, which

is locally called

'the

shooting of Nashoba Hill.'"

The same year,

Herbert J. Harwood published his Historical Sketch of Littleton, in

which he refers to Daniel Gookin’s 1674 observation of the rumblings as

follows:

"Traditions

are plenty of rumbling noises, sometimes said to be like the discharge

of cannon in the vicinity of Nashoba Hill." The same year,

Herbert J. Harwood published his Historical Sketch of Littleton, in

which he refers to Daniel Gookin’s 1674 observation of the rumblings as

follows:

"Traditions

are plenty of rumbling noises, sometimes said to be like the discharge

of cannon in the vicinity of Nashoba Hill."

These traditions

of noises associated with Nashoba Hill have survived up to the modern

era. On April 4, 1957, Carolyn Webster notes in her Littleton

Legends newspaper column that Nashoba Hill is

"a

curiosity because of the rumblings which have been known to emanate from

it in the past and in recent years."

Massachusetts Gazetteer, Nason & Varney, 1890

1821: An Altar on Nashoba Hill

Not long after

Rev. Edmund Foster had delivered his Century Sermon at the

Puritan (now Unitarian) Church in Littleton, a new denomination was

quietly filtering into town via Nashoba Hill. Although standing as a

pillar of the community today, the Baptists started out facing much

hostility. It is described on the Littleton Baptist website as

"the

great hatred and contempt which they met in certain quarters"

over their differences in doctrine and practice - which was essentially

a clash between Old Testament and New Testament beliefs. Prior to 1821,

there were only several Baptists in Littleton and they had to meet

secretly, and had no pastor.

View towards

Westford from the top of Nashoba Hill

One of these few

Baptists began weekly meetings with a believer from Westford and they

chose to do so secretly on the top of Nashoba Hill, which is the

boundary line between the two towns. On the spot between the two

parishes on the hilltop

"they

erected an altar of stone"

and began praying for a revival of religion in their towns. These

hilltop meetings took place from the early spring to late fall of 1819.

The first Baptist meeting hall in Littleton was dedicated in 1823.

1844: Signs & Wonders in Nashoba

The years between

1838 and 1844 were years of religious revival and wonder in Nashoba. In

1835 William Miller, a Vermont farmer turned preacher, began prophesying

that the end of the world would occur sometime between 1843 and 1844.

He gained a considerable following in Massachusetts particularly in the

Nashoba Valley area where he often preached the approaching Day of Doom

in the small brick Baptist Church in Littleton.

"Graves

will open up! Christ will reappear! There will be signs in the

heavens!,"

he thundered from the modest pulpit. The years between

1838 and 1844 were years of religious revival and wonder in Nashoba. In

1835 William Miller, a Vermont farmer turned preacher, began prophesying

that the end of the world would occur sometime between 1843 and 1844.

He gained a considerable following in Massachusetts particularly in the

Nashoba Valley area where he often preached the approaching Day of Doom

in the small brick Baptist Church in Littleton.

"Graves

will open up! Christ will reappear! There will be signs in the

heavens!,"

he thundered from the modest pulpit.

These Second

Adventists, or Millerites as they were more commonly called, set up

large encampments in Groton, and in Littleton (now Boxborough) in J. H.

S. Whitcomb’s pastures on the southeast side of Oak Hill Road. All

summer long the nightly singing, shouting, and occasional shrieking of

hundreds of fervent Millerites could be heard clear across Littleton.

It was

"the

craziest spot in Massachusetts,"

the locals averred. (Clara Endicott Sears, Days of Delusion,

1924)

William Miller 1848

.

Signs and wonders

did indeed follow the path of Miller’s teaching. Nashoba Hill was heard

to rumble and roar, as was noted at that time by Barber in Historical

Collections. And just as impressively, in April of 1843, a massive

comet appeared in the sky over the encampments. In January of 1844 the

encampments saw rings around the sun and blazing crosses in the sky.

The end was undoubtedly at hand. Possessions were given away and

good-byes said to non-believer friends and family. White robes were

donned, and after an aborted run on March 21, 1844, the Millerites

gathered on the night of October 22, 1844, to await being carried up to

heaven.

Robed Millerites

climbed

Gallows Hill in Salem, others gathered at graveyards, and still

more assembled naked on county hillsides. In Littleton the leading

Millerites, including the Richardsons of Westford, gathered at Benjamin

Hartwell’s house on the Common to await ascension and the end of the

world. The rank and file gathered at the Whitcomb farm encampment; or

the Old Burying Ground in Littleton Center to ascend with their dear

departed.

Littleton's Old

Burying Ground

.

Note 1: These were unsophisticated times

and the majority of the Millerites had trouble imagining how they would

actually ascend to heaven. Thus, many of them procured large

baskets and sat in them, supposing they would rise to heaven in the

basket. They also gathered at the cemeteries under the assumption

that their dearly departed would rise bodily from the grave and

accompany them to heaven in the basket. This resulted in the

event becoming quite the spectator sport wherein large crowds of

non-believers gathered at the cemeteries - including Littleton's Old

Burying Ground - to watch the Millerites and their dead rise to

God. The more sophisticated Littleton Millerites gathered at

Benjamin Hartwell's house across the street.

.

Note 2: This belief in the dead rising

corporally resulted in the end of at least one marriage. In an

account related by

Clara Endicott Sears, one fellow spent

the night sitting on the grave of his dead wife so he would be able to

ascend with her. His current wife, however, did not appreciate

this gesture, and upon the morning's light soundly rebuked her husband

and proceeded to terminate the marriage.

According to Clara

Endicott Sears in Days of Delusion, (1924),

"All

through the eventful summer of 1843 and 1844 long processions of

Millerites could be seen wending their way up the green slopes of some

hill back of their town or village, there to await or watch out for the

coming of the Lord."

Not unsurprising, there is a local legend that some Millerites so

impressed with the rumbles and roars of Nashoba Hill, considered to be

heralding the end of the world, that they were often seen on the hill

and spent the night on its peak awaiting the promised flight to heaven.

(Oral tradition.)

The prophesied end

did not come that night but panic did come to a congregation of

well-to-do Millerites at the Bancroft mansion in Westford. A local

joker named Amos Jackson, armed with his bugle, gave a mighty blast

outside the

building

at midnight. At the apparent summons of Gabriel’s

Horn, the white robed Adventists stumbled outside falling to their knees

while others cried and screamed hysterically. Amos supposedly greeted

them with a laconic,

"How

do,"

and walked home.

Sadly for many

Millerites, there was no home for them to walk back to come daylight.

They had given away all their possessions including their houses and the

new owners were not much obliged to return them.

|

William

Miller and the End of the World

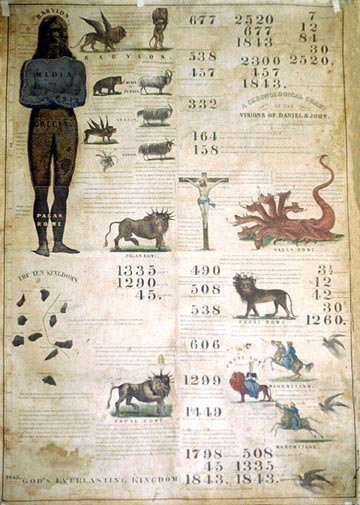

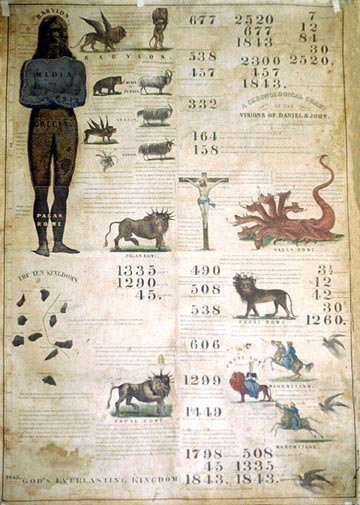

"1843

was to be the year of the world's end. In that year, Christ

personally would return to the earth to establish his kingdom,

glorify the saints, and take vengeance on the wicked. This

was the conclusion arrived at by William Miller in 1822 and the

message that he proclaimed for the next 21 years."

To the left is "Miller's

Prophetic Chart of 1843, published as a lithograph by B. W. Thayer

and Company. The large numbers indicate two different

methods of calculation that Miller used, both arriving at 1843 as

the year for fulfillment of the prophecy. The chart was

published in 1842."

1843 Prophetic Chart

As much as

William Miller wanted it to, the world never ended.

He even prophesied it three times with no luck. Sadly, he

seemed to have believed his own prophecy, and died a sad and

broken man.

William Miller and the Millerites seem

to weave their way through the fabric of the times I write about.

For other articles that have Millerites in the background

proclaiming doom , please see:

•

Deed Rock and Gods Ten Acres

•

How the

Shakers Invented Spiritualism

|

.Section 2: seismology

Modern Rumblings: An Epicenter

Nashoba hill still

booms. On January 23, 1990, I was living on Robinson Road at Littleton

Common, about one mile northwest of the peak of Nashoba Hill. There was

an extraordinary, explosive, all-pervading boom, and the house staggered

as though it had been struck by a car. Actually, it and the entire

Nashoba area had been struck by an earthquake centered in Littleton

registering 3.6 on the Richter scale. This was the strongest earthquake

recorded in Nashoba since the approximated 3.5 in December of 1668. And

I can tell you that Nashoba Hill does indeed boom.

Littleton-Nashoba:

A Seismic Epicenter

.

Note: Littleton is circled in

red. The yellow squares are

earthquakes, and the size of the square represents the relative size of

the earthquake. Note how Littleton is an island epicenter for a

cluster of midsized earthquake activity.

But at least

today, its booms are in conjunction with seismic activity. Nashoba has

always been an area of concentrated seismic events. The old

Newbury-Clinton Fault runs practically under Nashoba Hill as it passes

southwest between Littleton Common and Nagog Pond. For some reason, the

Littleton section of the fault is very active as an epicenter. In the

last 70 years alone, there have been at least twenty recorded

earthquakes centered in Littleton (Nashoba), averaging 2.2 on the

Richter scale.

The most recent, a

2.5 magnitude earthquake on October 19, 2007, was just over a mile

Southwest of Littleton Center. This was not without its sonic

component. Boston’s WCVB TV5 reported that concurrent with the

earthquake residents of Littleton

"heard

what sounded like a loud boom or explosion"

and that they also

"heard

rumblings"

later in the morning during an aftershock. The epicenter was only two

miles from Nashoba Hill, and exactly at the geographic center of the old

Praying Indian Village.

Plutons & Earthquakes

The October 2007

earthquake was reported on the news as a product of the Newbury-Clinton

fault. However, earthquakes in Eastern Massachusetts are of a more

complex origin. For starters, when I discussed the seismology of the

area with a geologist,

he informed me that the Newbury-Clinton fault is an artifact of a

previous age and has not been active in over a million years. The October 2007

earthquake was reported on the news as a product of the Newbury-Clinton

fault. However, earthquakes in Eastern Massachusetts are of a more

complex origin. For starters, when I discussed the seismology of the

area with a geologist,

he informed me that the Newbury-Clinton fault is an artifact of a

previous age and has not been active in over a million years.

Rather,

earthquakes in the vicinity are the product of geologic features called

Plutons. The pluton/earthquake connection was discovered in 1975 when

the Nuclear Regulatory Commission required Pilgrim Unit II in Plymouth,

Massachusetts to address the validity of seismic guidelines used in the

design of the plant.

Plutons – named after Pluto, god of the underworld – are 100 million

year old cylindrical shafts of cooled magma with depths of 30 miles or

more. It was found that all the major earthquakes in Eastern

Massachusetts and Southern New Hampshire centered on these plutons

(called the White Mountain magma intrusive series, and which are much

younger than most New England rocks).

Further, the

seismically active plutons were discovered to have magnetic and

gravitational anomalies. An aeromagnetic survey in 1975 confirmed that

these magnetic anomalies are circular and do indeed correspond exactly

with the circular tops of the pluton shafts.

Plutons &

Aeromagnetics: Ossipee Pluton

Note how the

circular plutonic rock shaft (top illustration) has a matching

circular magnetic anomaly (bottom illustration).

At its simplest,

the study found that where there are circular magnetic anomalies there

are plutons, and where these plutons also exhibit gravitational

anomalies is where (and only where) earthquakes occur in New England.

Magnetic Anomaly

Map: Magnetic Anomalies Correspond to Plutons

.

Note: Blue arrow

indicates the magnetic anomaly (Pluton) under Nashoba Praying Indian

Village. Also, the section of the Newbury-Clinton fault running

through Littleton is plutonic as well.

The earthquakes

themselves are caused by linear stresses pressing against the less

compressible rock (Gabbro) of the cylindrical plutons. This causes a

slight twitch in the pluton, which results in earth tremors.

Interestingly, in

Our New England Earthquakes (Weston Geophysical Corporation,

1977) an aeromagnetic map of New England reveals that the Nashoba

plutons follow the line of the old Newbury-Clinton fault. So although

the fault is not active, the plutons on it are.

Earthquakes in Nashoba

Certainly,

earthquakes have been recorded here in Nashoba since the earliest

Colonial times, and they have been recorded in conjunction with noise

activity, a significant piece of the puzzle.

The Littleton Town

Clerk’s report of 1896 referencing John Eliot, the man who organized the

Nashoba Praying Indian Village, had this to say,

"He

came to this place to visit his wards, and in his writings are found

allusions to it, among others to the noises in Nashoba Hill, and to a

great crack in the earth made here by an earthquake previous to 1670."

(Emphasis added.)

Eliot described

this crack as a vast

"hiatus"

in the earth that created immense

"cavities"

under the rocks. The location of this crack is unrecorded but it is

assumed it was somewhere on Nashoba Hill.

"A

great crack in the earth made here by an earthquake"

.

Note:

The above crack in the bedrock is several feet wide, up to 10 feet deep,

and over 150 feet long. When I first encountered it up by Black

Pond in Littleton I was sure I had found the vast earthquake-created

"hiatus" and "great crack" Eliot reported seeing in

Nashoba. Unfortunately, I have since learned that this is a very

early Colonial lime quarry, and the "crack" is where the lime seam ran before the lime

was picked out. Frankly, I was very skeptical of such a crack

being a lime quarry, or any type of a quarry, until I found pictures of

the old lime quarry in the Estabrook Woods over in Carlisle

that looks

exactly the same. So sad. In any event, here are some

links to early Colonial lime quarries in

Carlisle and

Chelmsford for comparison.

Nashoba Hill,

remember, means the Hill that Shakes. Gookin also equates the rumblings

of the hill with earthquakes,

"Some

have considered the hill adjacent as hollow, wherein the wind, being

pent, is the cause of this rumbling, as in earthquakes."

(Emphasis added.)

In 1890 Herbert

Harwood follows suit and equates the rumbling noises and sounds to the

"discharge

of cannon"

with seismic activity, referring to the noises as

"probably

earthquakes."

This is the

popular explanation for the noises and Littleton Legends

columnist Carolyn Webster concurs. In writing about the Nashoba noises

in 1957, she informs us that

"a

few years ago there were earth tremors felt at Cobb’s Chicken farm not

far from Nashoba Hill. Present day geologists advance their theories on

the booming of Nashoba, but so far none have been proven."

Cobb’s Chicken farm was located on Pickard Lane (at the present

Montessori School), which is about halfway between Nashoba Hill and

Nagog Pond.

Strange Lights

In conjunction

with the seismic activity, there have been reports of strange aerial

lights. This is not as odd as it may seem, as the theory of

"earthquake

lights"

has received considerable attention in the past few years.

In short, it is

thought that the pre-and post-seismic stresses, particularly in which

the

"explosive

process of rock fracture causes electrons emitted from fresh broken

surfaces to bombard the surrounding air and excite it to produce light.

This theory explains satisfactorily how both large and small earthquakes

which break the earth’s surface can produce light. Such phenomena as

bright white lights floating among treetops, luminous dust clouds moving

along near the ground, sequential flashes from different points on a

hillside, and fireballs on the horizon can be explained by earthquakes"

and are seen to appear at fault zones. In short, it is

thought that the pre-and post-seismic stresses, particularly in which

the

"explosive

process of rock fracture causes electrons emitted from fresh broken

surfaces to bombard the surrounding air and excite it to produce light.

This theory explains satisfactorily how both large and small earthquakes

which break the earth’s surface can produce light. Such phenomena as

bright white lights floating among treetops, luminous dust clouds moving

along near the ground, sequential flashes from different points on a

hillside, and fireballs on the horizon can be explained by earthquakes"

and are seen to appear at fault zones.

Earthquake lights: Turkey, 25 July 1999

Following the 3.1

magnitude earthquake in Nashoba on October 15, 1985 (described as

"the

rumblings of a freight train")

there appeared yellow-orange, brightly glowing pockets of air in the

Woodchuck Hill and Oak Ridge area on the Harvard-Boxborough border.

This part of the Oak Hill ridge is just a mile and a half southwest of

the old Nashoba Indian Praying Village and is high enough to have been

seen from the village.

Earthquake lights,

12 May 2008, Sichuan China

.

Note:

This video was taken 30 minutes

before the earthquake. (Click here for the

YouTube video)

Note the similarity of colors to the Woodchuck Hill lights of 1985 which

were reported as being "yellow-orange."

Further, at the

time of the November 23, 1980, Nashoba earthquake of 2.5 intensity, I

observed at night from the vantage point of Nagog Pond a bright

welling-up of intense white light out of the top of Fort Pond Hill (in

what is now called the Sarah Doublet Forest), in the heart of the old

500 acre reservation. This welled up like a dome of light, about 350

yards wide, and about 200 yards tall at its peak. After about three

seconds the light then collapsed back into the earth. This was observed

with a friend.

Nagog Pond: view of

Sarah Doublet Forest from across the water

.

Note:

The light-dome anomaly was

seen over the trees on the far left shore.

Since I have been

presenting this topic as a slide show in Littleton and surrounding towns

a number of people have come forward to share with me their own

experiences with light phenomena in Nashoba. For example, an elderly

man on Star Hill in Littleton had light balls roll through his house one

night, and an employee at Nashoba Hill Ski Area in Westford describes

seeing a recent dome of light at Nagog Pond similar to the one I saw.

Earthquake lights,

26 September 1966, Mount Kimyo, by T. Kuriayashi

.

Note:

Compare this image to the descriptions of

glowing domes of light seen at Nagog.

Going back to the

fact that Eliot allowed the Indians to make their own choice of location

for their praying villages, they certainly chose a place in

"nashope"

where many strange and wondrous characteristics are concentrated and

occur regularly:

•

Rumblings and

hummings from the earth.

•

Seismic

activities.

•

Strange light

phenomena.

It seems unlikely

that this is coincidence.

.Section 3: The Moodus Noises

There is a Bad Noise

The lights,

rumblings, and earthquakes at Nashoba are hardly without precedent.

Indeed, this has been going on in a place known as Moodus, in East

Haddam, Connecticut for as long, and with much more attention.

Moodus is an

abbreviation of Machemoodus which in the local Wangunk dialect means

"there

is a bad noise,"

a reference to the strange sounds heard there. These noises were

recorded by Colonials as early as 1668, and centered on Mount Tom,

located on a neck of land between East Haddam and the Village of Moodus,

all of which was purchased form the Indians in 1662.

|

Mount Tom, Haddam

Connecticut

.

Note:

Mt. Tom and Nashoba

Hill are quite similar in size. Mt. Tom at 314 feet in

height rises 214 feet above the Connecticut countryside, while Nashoba Hill at 426

in height rises 226 feet above the Massachusetts countryside.

Also, both hills are composed of the same geologic materials:

Schist and Gneiss.

.

The Counties both Nashoba Hill and

Mount Tom are located in are called Middlesex County. I do not

attribute any particular significance to this, but it is an odd

connection worth mentioning.

|

These noises were

described at the time as crackings and rumblings that were compared to

fusillades, to thunder, a roaring in the air, to the breaking of rocks,

to reports of cannon, and to rocks falling into immense caverns and

bouncing

off underground

cliffs as they fell. Sometimes the sounds and tremors would roll

out of the north and pass underneath, and break like a severe

thunderclap,

"shaking

the houses and all in them."

These were so numerous that the Reverend Hosmer, the first minister in

Haddam, wrote in 1729 that he had heard several hundred such noises both

"fearful

and dreadful"

within twenty years, sometimes daily.

Earthquakes & Lights

The region of

Moodus is one of the three most seismically active places in New

England, the others being Ossipee, New Hampshire, and northeastern

Massachusetts including the Nashoba Hill area. John Eliot records in

his diary a series of earthquakes including the now familiar attendant

noises and aerial lights.

"On

November 4, 1667, there were strange noises in the air, like guns and

drums, and on March 16, 1668, and earthquake shock was felt after there

had been prodigies [extraordinary objects, probably light phenomena] in

the heavens the night before."

These noises and vibrations were intense enough to agitate the waters of

the river.

|

The Moodus Noises Cave

According

to local legend, the Moodus Noises can be heard most clearly issuing

from the cave on Cave Hill, which is adjacent to Mt. Tom. The site

is owned by the

Cave Hill Resort in Moodus, Connecticut. For more on the

Moodus Noises,

see

here. According

to local legend, the Moodus Noises can be heard most clearly issuing

from the cave on Cave Hill, which is adjacent to Mt. Tom. The site

is owned by the

Cave Hill Resort in Moodus, Connecticut. For more on the

Moodus Noises,

see

here.

Entrance to "Moodus Noises" cave on

Cave Hill, 1940s

|

Concerning a 1663

earthquake felt all the way in Montréal, the French relate that

"Ten

days after the initial shock, a loud rumbling noise was heard. Forest

trees were set in violent motion, thrown from side to side. There were

flashes of lightening and rocks cracked and rolled over each other."

A 1797 earthquake

in Moodus resulted in

"stones

of several hundred tons found removed from their places and fissures

were found in immovable rocks."

A Prodigious Trade at Worshiping the Devil

Indian Pawahs

(powwows) were seen as priests with certain powers. According to James

Mavor and Byron Dix in Manitou (1989),

"They

could make

'rocks

move'

and

'trees

dance.'"

This sounds uncannily like the above-quoted descriptions of seismic

activity upon rocks and trees in the 1663 and 1797 earthquakes, and in

significant earthquakes in general. Surely there is a link between

Indian shaman and earthquakes.

According to Mavor

and Dix, the Indians local to Moodus were

"known

for their religious activity and served as priests or shamans to other

tribes. Pequot, Mohegan, and even Narragansett Indians, with whom the

other groups were constantly in conflict, went to Moodus and the

Machemoodus powwows because they believed that the thunderings and

quaking, called Moodus noises, could only mean that this was the home of

Hobomock, the spirit most sought after by the powwows of New England.

The English colonists, as early as 1670, reported both the noises and

extraordinary Indian ritual activity on the mountain [Mount Tom]."

Mt. Tom by E. A. Coates

Revered Hosmer

describes Moodus in 1729 as

"a

place of extraordinary Indian pawaws, or, in short, that it was a

place where the Indians drove a prodigious trade at worshiping the

devil."

In other words, Moodus was a significant and important questing ground

for native shamanic activity.

Hobomock

Hobomock was one

of two principle deities of the Algonquin-speaking peoples of New

England, the other being Kichtan. Kichtan was not seen or prayed to but

was understood to be good. Hobomock was seen and prayed to and was of a

more earthy and ambivalent quality. He was not a devil as such (the

Indians had no devil figure) but was rather a dark and powerful side of

nature. Hobomock was one

of two principle deities of the Algonquin-speaking peoples of New

England, the other being Kichtan. Kichtan was not seen or prayed to but

was understood to be good. Hobomock was seen and prayed to and was of a

more earthy and ambivalent quality. He was not a devil as such (the

Indians had no devil figure) but was rather a dark and powerful side of

nature.

The Indians prayed

to him to heal wounds and cure diseases, and when a disease was curable,

Hobomock was considered responsible for both the condition and the

cure. If it was not curable, it was considered the will the Kichtan.

As the most

day-to-day operative spirit, Hobomock was the most sought after deity in

vision quests by the powwow shaman. He was invoked musically, and with

rhythmical practices, and was said by the successful spirit quester to

protect and empower those who obtained visions of him. However, to

Puritan eyes, those who sought visions of Hobomock were perceived as

seeking the devil.

Of Witches and the King Under the Mountain

Legends of Puritan

times relate that witchcraft was at the root of the Moodus noises. It

was said that the Haddam Witches, who practiced black magic, met the

Moodus witches, who used white magic, in a cave beneath Mount Tom, and

fought them in the light of a great carbuncle [gem] that was fastened to

the roof. If the-witch fights were continued too long the King of

Machimoddi [Machemoodus], who sat on a throne of solid sapphire in the

cave whence the noises came, raised his wand: then the light of the

carbuncle went out, peals of thunder rolled though the rocky chambers,

and the witches rushed into the air. Legends of Puritan

times relate that witchcraft was at the root of the Moodus noises. It

was said that the Haddam Witches, who practiced black magic, met the

Moodus witches, who used white magic, in a cave beneath Mount Tom, and

fought them in the light of a great carbuncle [gem] that was fastened to

the roof. If the-witch fights were continued too long the King of

Machimoddi [Machemoodus], who sat on a throne of solid sapphire in the

cave whence the noises came, raised his wand: then the light of the

carbuncle went out, peals of thunder rolled though the rocky chambers,

and the witches rushed into the air.

Note:

Hobomock

apparently had several such dwellings. Twenty-two miles to the west of

Mount Moodus is

"the

sleeping giant,"

Mount Carmel – a series of hills that resemble a human form in repose

(not unlike Ute Mountain in Colorado where the

"great

warrior god"

sleeps). The local Quinnipiac Indians were said to believe that

Hobomock was sealed within Mt. Carmel for diverting a river by

stamping his feet – an act that sounds suspiciously like an

anthropomorphicized

description of a powerful earthquake.

Mount Carmel: "The

Sleeping Giant"

.

Note: The series of hills

gives the impression of a large figure in profile sleeping on its back.

The Moodus account

is interesting in two respects. First, it pits the witches of

Haddam, a town, against the witches of Moodus, the woods.

Uniformly, English dwelled in towns, and Indians dwelled in the woods.

In an odd, almost Freudian, reversal of Puritan thought the black magic

witches were the English and the white magic witches were the Indians.

Second, and more

germane to our topic, the King

"of

the bad noises"

resides enthroned within the Mountain itself, wherefrom emanates the

rumblings and explosive thunderclaps. To quote Mavor and Dix, who

also came to the same conclusion that Hobomock resides within the

rumbling hill, the shaman sought Hobomock

"especially

in locations such as the summit of Mount Moodus [Mt. Tom], where the

depths of the mountain are considered the home of Hobomock, who makes

the bad noises."

The Voice of Hobomock

Hobomock was

certainly sought after, especially in places like Mount Moodus, which

was considered his abode. He could speak in subterranean thunderings,

as well as through the quiet subtleties of rocks and stones. There are

a number of perched stones in the Moodus area. Given even the slightest

tremor, these will gently rock, which was an indication of the spirit of

his presence to the discerning shaman.

Mt. Tom by Charles Farrer 1865

Certainly the

rumblings and rockings were the manifestations and voice of Hobomock and

shaman came from all over New England to seek him in such places with

the qualities of Moodus.

However much he

was sought, the shaman sought to appease his more powerful eruptions by

carving symbols of the Wakon-bird (spirit-dove) with special quartz

crystal* spirit-stones (according to Mavor and Dix in Manitou).

.

*Note:

White quartz is certainly found on Mt. Tom, as evidenced by

this picture.

The power of

Hobomock to move the rocks and trees became associated with the

Hobomock-seeking shaman of seismically active areas. Thus it is no

exaggeration, spiritually, that their powers were specifically said to

be the power to make

"rocks

move"

and

"trees

dance."

It is an identification with the powers of their deity, and places like

Moodus were these shaman’s sacred sites. The power of

Hobomock to move the rocks and trees became associated with the

Hobomock-seeking shaman of seismically active areas. Thus it is no

exaggeration, spiritually, that their powers were specifically said to

be the power to make

"rocks

move"

and

"trees

dance."

It is an identification with the powers of their deity, and places like

Moodus were these shaman’s sacred sites.

Mavor and Dix

concur in Manitou,

"The

history of the Moodus area attests to participation of the native

shamans with a geophysically active landscape that moved and produced

[noises] and light. This follows a pattern among cultures all over the

world that have attributed religious significance to glowing forms that

appear at areas of recurring earthquakes."

Algonquin Shaman

.

Charles M.

Skinner, in Tales of Puritan Land (1896) links Moodus back to

Nashoba, as follows,

"Such

cases are not singular. A phenomena similar to the Moodus noises, and

locally known as

"the

Shooting of Nashoba Hill,"

occurs at times in the eminence of that name near east Littleton,

Massachusetts. The strange deep rumbling was attributed by the Indians

to whirlwinds trying to escape from caves."

.Section 4: A Sacred Place of Vision Quest

Nashoba: Saving it from the English

Skinner is correct

to cite Nashoba Hill. Nashoba Praying Indian Village bears all the same

qualities as Moodus, except on a smaller scale. It is an epicenter of

seismic activity from the earliest recorded times up to the present;

there is a hill that rumbles and thunders; light phenomena are seen here

in conjunction with earthquakes; and it is a site specifically chosen by

the Indians themselves.

Recall that Eliot

allowed the Indians of 1651 to chose the locations of their new

villages. These sixteen square mile plantations were granted by deed to

Indian ownership, thus protecting them from the usual encroachment and

overrunning typical of the land-hungry English. When Sachem Tahattawan

chose

"nashope,"

its close proximity to Concord was questioned. Eliot thought they would

have preferred a location that was further away, with more game, and

with less encroachment from the English. Eliot questioned Tahattawan on

this but Tahattawan was adamant.

"Nashope"

it would be. Recall that Eliot

allowed the Indians of 1651 to chose the locations of their new

villages. These sixteen square mile plantations were granted by deed to

Indian ownership, thus protecting them from the usual encroachment and

overrunning typical of the land-hungry English. When Sachem Tahattawan

chose

"nashope,"

its close proximity to Concord was questioned. Eliot thought they would

have preferred a location that was further away, with more game, and

with less encroachment from the English. Eliot questioned Tahattawan on

this but Tahattawan was adamant.

"Nashope"

it would be.

John Eliot

It seems likely,

considering the circumstances involved, that Tahattawan was using the

opportunity to reserve away a site sacred to Hobomock from being overrun

by the English. However sincere he may have been as a convert, he would

also have been savvy enough to take advantage of the opportunity

presented him. After all,

"nashope"

was his principle residence, and he would have been more aware then

anyone of its significance.

Also, as a

permanent village site, which a Praying Indian Village would be, it was

lacking the game required to support a community. Traditional Indian

ways were to move their villages several times a year to follow the

seasons of harvest and game. Clearly, there were other factors involved

with the selection of Nashoba Indian Plantation.

Mavor & Dix Indian

Village / Seismic Activity Map from Manitou

.

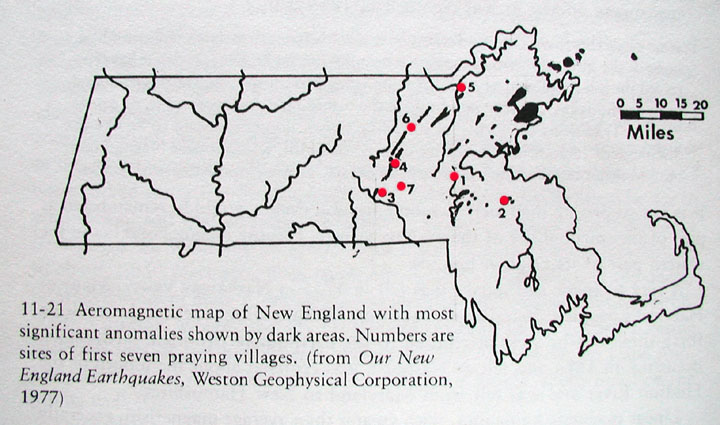

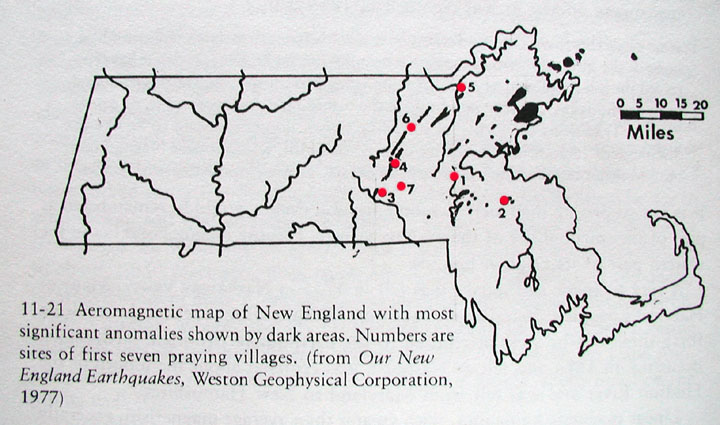

Note 1: The red dots show the locations of

the first 7 Praying Indian Villages. Mavor & Dix have drawn-in

both magnetic anomalies and rivers. (For the purposes of this map

ignore the rivers.) The map shows that the 7 Villages fall on or

adjacent to magnetic anomalies (and therefore plutons and are thus on

seismically active locations).

.

Note 2: Mavor & Dix in Manitou call

the above seismically active magnetic anomaly locations "linear faults."

Rather, these should be termed plutons per the discussion on this

webpage. The magnetic anomalies marked on the above map were

however coped from the Our New England Earthquakes map, and

therefore do mark plutons and not faults. Only the plutons, and

not faults, are seismically active in Massachusetts at this time, so although the

terminology is incorrect, the Mavor & Dix argument is still sound.

Another

interesting fact about the locations of the Praying Indian Villages is

that the early ones at least may all have been situated at sites chosen

by the Indians for special qualities. When Mavor and Dix laid out the

original seven Indian Plantation on a map of seismic activity, they

noticed that four of the villages (including Nashoba) fell on linear

faults, while another two were adjacent to anomalies.

"This

impressive correlation of seismic activity with the locations of the

praying Indian villages supports our theory that these places were

selected in part because of their seismic activities, which indicated

that they were abodes of the spirit Hobomock."

(Mavor and Dix, Manitou.)

Nashoba: A Ritual Landscape

It is my opinion

that the Praying Indian Villages - especially Nashoba - were located at

sacred places chosen by the Indians at areas that they knew and that

they and their ancestors had ritualized.

Is there any

indication of such ritualization at Nashoba? The answer is yes.

For starters,

there were eight underground stone chambers local to the old Indian

Plantation: six in Littleton, one in Harvard, and one in Acton. Of the

six that fell within the exact bounds of Nashoba Plantation,

two of the

ones in Littleton have since been destroyed, and another Littleton

chamber since lost (said to have been at the Northwestern foot of

Nashoba Hill).* There are chambers in Moodus and Mavor and Dix consider

these and other chambers to be

kiva-like vision quest sites. One of the

Littleton chambers is in the Sarah Doublet Forest, the heart of the old

sacred landscape of Nashoba.

.

*Note: The eight chambers of the Nashoba

area are: Whitcomb Ave Chamber 1, Whitcomb Ave Chamber 2, Partridge Lane

Chamber, Sarah Doublet Chamber, Nashoba Brook Chamber, the destroyed

King Street/495 dogleg Chamber, the Tahattawan Road/Foster Street

Chamber, and the lost Nashoba Hill Chamber.

Whitcomb Avenue

Chambers 1 & 2 in Littleton

.

Note 1:

The Whitcomb Avenue Chamber 1, to the left, is on a

hillside and overlooks the Boxborough Esker site. Unfortunately,

due to the sighting lines being

blocked by a

large red barn, it is unknown if it is oriented to view a

significant sunrise over the esker. However, with the advent of

GoogleEarth, calculations can be run to recreate the sightlines and

determine significance if any.

.

Note 2:

The Whitcomb Avenue Chamber 2, to the right, is adjacent

to the Whitcomb house. The Whitcomb house was built in 1705 and

is the earliest Colonial structure in the vicinity. The chamber has

had many uses over the years. It

was briefly used as a tomb by the Whitcomb

family until around 1925 when some collage boys broke in and stole a

bone. It was also used by a Mr. Whitcomb of years gone by to play the

trumpet in. The chamber originally had a walk-in entrance, as

evidenced in this

31 May 1932

photo by

Harriet Merrifield Forbes. The chamber is next to a brook,

and at the time of the walk-in entrance, the floor of the chamber

would have been roughly level with the brook, and thus prone to flooding

- a fact that would have made it a very poor "Colonial root cellar." Interestingly, and perhaps significantly, there is a 40

foot stone

tunnel in the immediate vicinity of the chamber. The tunnel is

partially filled and is collapsed in the middle, but as recently as the

1970s boys were able to crawl a good 12 to 15 feet into it. Local

folklore is that it was

constructed as an escape route to the chamber in the event of an Indian

attack.

Dogleg Chamber in

Harvard

.

Note:

A length of the entryway of this chamber has long since

collapsed. Originally, in the above right photo, the crawlway came

in from the left and crossed to the current opening, and made a left

hand turn into the current opening. Here is a

sketch

from Manitou of the current tunnel and chamber configuration.

There is legend of a second chamber adjacent to this one that was

destroyed by Partridge Road. Also, there is reason to believe that

this chamber was used in Underground Railway times as a way station.

For a picture of the crawlway, see

here.

(Did you see the big hairy spider?) The chamber itself is large enough to stand up in. As a matter of

fact, when Partridge Lane was being surveyed for house parcels, the

surveyors had lunch one day in the chamber.

Nashoba Brook

Chamber in Acton: Collapsed & Reconstructed

.

Note:

The Nashoba Brook chamber, which had a

partially collapsed entryway, was

reconstructed in

2006 by the Acton Historical Chamber with assistance from

NEARA. Professional

archeologists and historians associated with the project erroneously

maintained that the chamber was within the bounds of the Nashoba Praying

Indian Plantation, and made this part of their reports. Clearly,

they never looked at the historical record, the Littleton Proprietor's

map, or bothered to even review the deeds involved. The chamber,

though in the Nashoba area, is more then a mile and a half from the easternmost

corner of Indian Plantation. Sadly, several chowderheads in NEARA

continue to chant this error as religious dogma.

Interior of

Whitcomb Avenue Chamber 1 & the Nashoba Brook Chamber

.

Note: For a picture

that captures the surprising size of the roof slabs of the

Whitcomb Ave Chamber 1, click

here.

For an interior shot of the Whitcomb Ave Chamber 2, see

here.

Interior shots of the Nashoba Brook Chamber are

here and

here.

|

Sarah Doublet's

Cave Sarah Doublet's

Cave

By

Daniel V. Boudillion

14

December 2009

There is an oral tradition in Littleton

that Sarah Doublet (the last Indian to hold title to the 500 Acre

Indian Reservation) lived in a cave somewhere in what is now the

Sarah Doublet Forest. The problem with this is there was

known cave in the area - indeed, I myself had walked the land

hundreds of times since the late 1970s and did not believe for an

instant there was even the possibility of a cave up there.

Other people I knew wove convoluted theories that her "cave" was

actually a lean-to of branches up against a large boulder, for

example.

This all changed one Spring morning in

the early 1990s when I was out for a walk in the Sarah Doublet

Forest.

For the rest of the article click

here.

|

Also in the Sarah Doublet Forest is a

mammoth boulder resting on bedrock. This appears similar to the perched

rocking stones in Moodus, the kind of stones that would respond with

rocking, however slightly, to even the most otherwise undetectable earth

tremor and

"Voice

of Hobomock."

There is another smaller perched boulder near the southern shore of

Nagog Pond.

Harvard Rocking

Stone & Nagog Perched Boulder

.

Note: The Harvard

rocking stone, located in South Shaker Village, is approximately 1 ton

and can be set in motion with the finger of one hand. The Nagog

perched boulder appears to be a rocking stone. Forest detritus has

built up on the platform at it has very little movement at the moment.

Sarah Doublet

Forest Perched Boulder

.

Note: This huge

boulder appears to have slipped off its platform, perhaps in an

earthquake? It is my theory, based on the similarities with

Moodus, that this was at one time a rocking stone as well. It is

located on top of the hill over looking the area.

Another ritual

site is in Boxborough (originally part of Littleton), a little more than

a mile away from the Sarah Doublet Forest, but still within the bounds

of the old Indian Plantation. This site is a solstice sunrise site.

From a stone slab viewing platform (if you care to venture out on the

morning of the winter solstice) you will observe the sun rising across a

field from a notch in the halves of a large outcrop of bedrock. There

is also a midsummer solstice sunrise that can be viewed from the

platform, but it is less spectacular and less convincing.

Half Moon Meadow Brook Winter Solstice

Sunrise Site

.

Note: Sunrise Rock,

left, is a large boulder/bedrock formation. The sun is

observed to rise in the notch in the rock as evidenced in the picture to

the right. Click pictures to enlarge.

|

Half

Moon Meadow Brook: Half

Moon Meadow Brook:

A

Sunrise Solstice Site

Field Report by Daniel V.

Boudillion

On December 22, 2001 at 7:30 a.m.,

approximately thirty people gathered in a field in Boxborough to

watch the winter solstice sun rise majestically through an

alignment of stone structures. The outing was sponsored by the

Sudbury Valley Trustees and led by George Krusen.

Half Moon Meadow Brook is a lithic site

located in Boxborough, Massachusetts, and may well be one of the

most significant early sites in Middlesex County. Its most

outstanding feature is its spectacular winter solstice sunrise

alignment. There is also a summer solstice sunrise alignment and

a variety of interesting and enigmatic stonework.

For the rest of the article click

here.

|

Interestingly, the

1725 deed from Isaac Powers Junior into Samuel Dudley shows that at that

time there was an Indian trail running between the Indian New Town at

the Sarah Doublet Forest and the solstice sunrise site, or Half Moon

Meadow Brook as it is called today. It is recorded as

"…the

Path that runs from Benjamin Hoar to Joseph Blanchard."

This

"path"

is now Newton Road and Boxborough Road.

Isaac Powers junior

to Samuel Dudley, February 24, 1724

.

Note: The

deed goes on to run as follows: "...the

Path that runs from Benjamin Hoar to Joseph Blanchard then running

Northerly by said Path till it comes to a stake and heap of stones then

bounding on Benjamin Hoar across Rattlesnake Meadow..."

Rattlesnake Meadow is the marsh at Fort Pond at the corner of Newtown

Road and Boxborough Road, which can be seen

here.

It was so-called because of the rattlesnake problem in the area in those

days. However, by 1850, the rattlesnake had been systematically

exterminated in Massachusetts. For more on Rattlesnake named

places in Littleton, see:

Looking For

and Finding Littleton's Rattlesnake Hill.

Blanchards & Witchcraft: Location, Location,

Location

The Blanchard name

is well-known and respected in Boxborough, but perhaps less well known

is the fact that Joseph’s three daughters Elizabeth (11), Joanna (9),

and Mary (7) were involved in the last recorded instance of Witchcraft

accusations in Massachusetts. This happened in 1720, when the Blanchard

girls accused Abigail Dudley, the wife of Littleton’s Town Clerk and

Selectman, Samuel Dudley, of bewitching them. It created more than a

local stir and the girl’s drew an avid audience that relished the

spectacle of them falling into fits and allowing themselves to be found

in odd places such as ponds and rooftops, supposedly transported there

by Mrs. Dudley’s witchcraft. The Blanchard name

is well-known and respected in Boxborough, but perhaps less well known

is the fact that Joseph’s three daughters Elizabeth (11), Joanna (9),

and Mary (7) were involved in the last recorded instance of Witchcraft

accusations in Massachusetts. This happened in 1720, when the Blanchard

girls accused Abigail Dudley, the wife of Littleton’s Town Clerk and

Selectman, Samuel Dudley, of bewitching them. It created more than a

local stir and the girl’s drew an avid audience that relished the

spectacle of them falling into fits and allowing themselves to be found

in odd places such as ponds and rooftops, supposedly transported there

by Mrs. Dudley’s witchcraft.

As the summer wore

on a formal complaint of Witchcraft loomed against Mrs. Dudley.

However, Mrs. Dudley died in childbirth on August 9, 1720 before any

such formal accusations were lodged. In 1728 Elizabeth Blanchard

confessed to false accusations on her part to the Reverend Ebenezer

Turell in Malden, where the Blanchard family had moved for several years

following the events.

The girl’s fits

and accusations played out at their home on Depot Road in

Boxborough, which was part of Littleton at the time. The Blanchard

homestead was situated in what is now the front yard of George Krusen’s

colonial, itself a Blanchard house.

Blanchard

House, Depot Road, Boxborough

.

Note:

The original Joseph Blanchard house of 1718 stood between the current

structure and road. It is known that John Blanchard built the

current house in 1844/45 using beams and planks from the original

home. A recent dry spell revealed the footprint of

the original foundation between the house and road.

In a strange

twist, the Half Moon Meadow Brook Winter Solstice site is on the site of

the old Joseph Blanchard farm and only a hundred yards from where the

original house was located and the witchcraft fits and accusations

played out.

Winter Solstice Sunrise at Half Moon

Meadow Brook

.

Note: In

these photos of the Winter Solstice sunrise, an anomalous green orb is seen to move across the meadow.

|

1720 Littleton: the Dudley Witchcraft

Affair

By

Daniel V. Boudillion

31

October 2009

The Town of

Littleton was barely 6 years old when it was rocked in 1720 by

accusations of Witchcraft. The young daughter of Joseph

Blanchard, followed by her two younger sisters, exhibited

outrageous afflictions and behaviors that they attributed to the

machinations of a witch. Ultimately they accused Mrs. Abigail

Dudley, the wife of Littleton’s first Town Clerk and Selectman,

Samuel Dudley, as their diabolical tormentor.

In the

process, the Blanchard home became a sideshow of

"afflicted"

behavior: fortune telling, trances, fits, levitation, invisible

attacks, retaliations, and rocks flung down the chimney (and into

the soup!). People came from miles around for the cheap

entertainment and the majority opinion was Witchcraft, and a

formal lodging of accusations loomed against Mrs. Dudley. She, in

turn, had the audacity to die in peculiar circumstances before any

such charges could be lodged against her and a trial executed –

but yet strange deaths and suicides have dogged the descendents of

Joseph Blanchard ever since.

Forthcoming article by Daniel V.

Boudillion, currently being presented locally as a slide show.

For an introduction to the Dudley

Witchcraft Accusations see

Ceremonial

Time: Fact or Fiction? An Inquiry into John Hanson Mitchell.

|

Boxborough Esker

Blanchards and

Witchcraft aside, there is another special site within the bounds of the

old Indian Plantation. This is located in Boxborough but was

originally part of Littleton. The site is a series of three large

earthen circles, each surrounded by a ditch, that Mavor and Dix believe

to have Indian ritual significance. It is located next to Muddy

Pond on the eastern side of the Boxborough esker on Beaver Brook.

It is significant that this esker runs its length dead-center along the

Newbury-Clinton fault. In fact, some geologists think certain

fault-line eskers are the result of

soil

liquefactions in high magnitude earthquakes rather then glacier

related soil deposits.

Top of Boxborough

Esker & Earthen Circle at base of Esker

.

Note:

The the earthen ditch-and-circles are very subtle and difficult to see

in person, let alone capture in a photograph. Your best bet is to

visit the location in the late fall or early spring at dawn. The

early morning shadows will help define the shapes so you can see them

better.

Prayer Seat at

Boxborough Esker on left & example of a Prayer Seat in good condition on

right

.

Note: The prayer seat on the left is at the

base of the Esker. The one on the right is shown as an example of

a Prayer Seat in good condition. See the

Picture

Glossary of New England Lithic Constructions for further information

on Prayer Seats.

Whatever the

cause, there are several stone prayer seats here, much like at Moodus,

and a summer solstice sunset alignment as well. The following statement

from Mavor and Dix in Manitou sums up well their views and

interest in the lands of the Nashoba Indian Village:

"We

believe that the shaman-preachers of Nashoba used the praying villages

to maintain the Indian communication links, the sacred landscape and the

stone and earthen structures in the midst of encroaching white

colonists. We believe that central to their world was the Boxborough

esker."

I disagree on the

"centrality"

of the Boxborough esker. Certainly it was important, perhaps

ritualistically, but I feel the Nagog area was more central to the

natural intrinsic uniqueness of Nashoba.

|

The

Boxborough Esker: A Featured Site in Manitou The

Boxborough Esker: A Featured Site in Manitou

Field Report by Daniel V. Boudillion

The Boxborough Esker is

prominently featured in the book Manitou by James Mavor and

Byron Dix. They consider it a significant Native American site in

the Hopewellian tradition. To quote the authors:

"We

believe that the shaman-preachers of Nashoba used the praying

villages to maintain the Indian communication links, the sacred

landscape and the stone and earthen structures in the midst of

encroaching white colonists. We believe that central to their

world was the Boxborough esker."

I thought it would be interesting to

visit the esker and report how it appeared to me. It is not my

intent to prove or disprove anything with this article, but simply

to report what I saw and provide some photos for those who have

not yet visited the site.

For the rest of the article click

here.

|

An Island of Granite in a Sea of Schist

The entire region is an

area of sedimentary schist and gneiss that extends 21 miles from Lowell